Boas and the Logic and Sociology of Scientific Inquiry

Boas must, first of all, be

understood as a fieldworker, according to George W. Stocking, Jr.

Departing from Tylor, and previous anthropological thought, and minimizing

the role of cultural evolutionary schemas, Boas’ revolutionized anthropology

by contributing to a modern understanding of culture(s) as shaped

by history, as plural, holistic, behaviorally determined and relativistic.

Inherent in this conception of culture are some ideas that imbricate

irregularly with the logic of scientific inquiry. This paper attempts

to articulate some of the ways hybrid anthropology, which draws approaches

from both scientific and historical inquiry, works. In particular

this paper examines some ways in which the field worker Boas’ revolutionary

conception of culture interplays with Stanley Tambiah’s conception

of scientific inquiry, sociology and logic. Tambiah asks where social

scientific inquiry logically fits in the schema of scientific inquiry

and society. This paper attempts to rework, refine and bring into

relief the seminal, anthropological Boasian culture concept with the

logic and sociology of scientific inquiry.

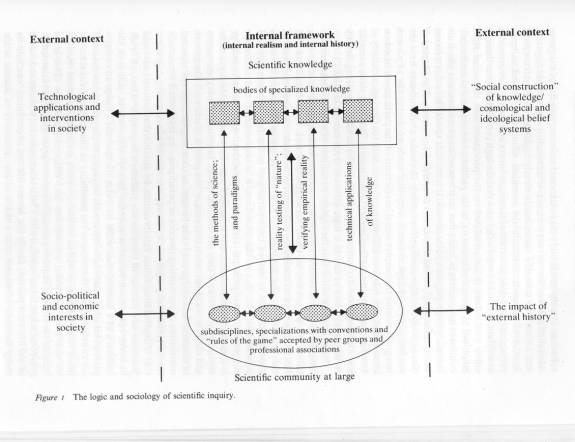

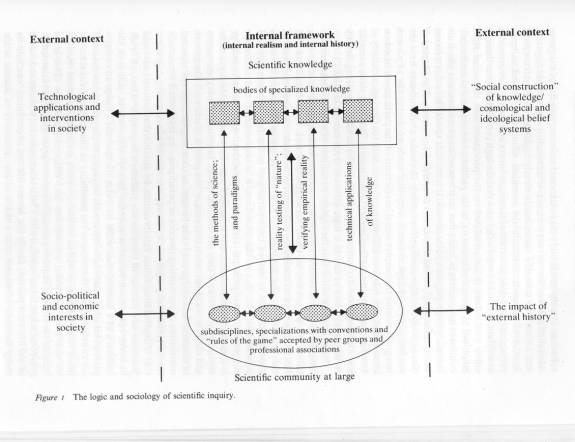

In “Magic, Science, Religion, and the Scope

of Rationality,” Harvard anthropologist Stanley Tambiah examines the

logic and sociology of scientific inquiry. Tambiah identifies (see

figure below) the internal framework of scientific inquiry as a collection

of relations between, on the one hand, bodies of specialized knowledge

(rectangles) and, -- on the other, subdisciplines, specializations

with conventions and “rules of the game” (ovals) accepted by peer

groups and professional associations (see figure). I want to examine

the implications -- for Boasian anthropological understandings of

culture and fieldwork in terms of the relation between data and text

embodied in the bodymind of the fieldworker -- and for scientific

inquiry as outlined in Tambiah’s chart. By contextualizing each understanding

in the other, I want to examine how anthropology functions as a social

science -- its ‘scientific’ limitations and problems and why anthropologists

haven’t seemed to have been conducting scientific inquiries in the

last 50 years or so -- as well as the limitations of Tambiah’s theoretical

framework of the logic and sociology of scientific inquiry in terms

of Boas’ anthropological culture conception.

Contextualizing Boasian sociocultural anthropology within Tambiah’s

framework helps to highlight both strengths and weaknesses of sociocultural

anthropology as a mode of scientific inquiry. Since Boas’ culture

concept continues to be significant today, imbricating Boas and Tambiah

potentially points out new research directions for anthropology or

at least clarifies known approaches. In terms of Boas’ concept of

culture, I want to look at his methods and paradigms of anthropology

in terms of scientific inquiry (Tambiah’s internal framework).

As a ‘scientific’ field worker, Boas engaged in anthropological “data

– text” formulations based on a culture concept informed by behavioral

determinism. Studying Pacific Northwest Native American traits and

myths, Boas suggested that behavior is shaped by habit, and that tradition

is a shackle informing these habits. In this model, the Boasian anthropological

interaction between the rectangles and ovals (see figure) – i.e. the

methods of science, paradigms (field work), reality testing of “nature,”

verification of empirical reality, and technical applications of knowledge

– would typically refer to the ‘Boasian’ field worker him/herself

participating, observing, and taking notes filtered through a behaviorally

determined, tradition-binding conception of culture – which, for Boas,

binds less when understood. This culture conception is also plural,

holistic, historic and relativistic, and typically learned in an academic

environment. The Boasian field

worker would then transcribe his or her data into text typically from

an analytical standpoint such as an examination of myths, traits or

habits.

In terms of Tambiah’s figure (below), the point I want to make has

to do with the way the external context and internal framework of

science interplay in terms of Boas’ culture concept. Boas’ culture

concept seems to suggest that the habits, traits and words (as a body

of specialized data in the internal framework of scientific inquiry)

imbricate rather than adjoin the external context (plural,

historically constructed, relativistic habits or traits). The distinction

between internal and external is more ambiguous or contingent than

Tambiah depicts it to be. In addition, “the impact of “external history””

in Tambiah’s chart (bottom right) would articulate with the subjects’

‘habits’, as “bodies of specialized knowledge” (see chart, top center),

which the Boasian fieldworker observes in the field – in that ‘habits’

arise from particular histories - an ‘arrowed’ interaction which Tambiah

doesn’t identify in his figure.

In the context of the logic

and sociology of scientific inquiry, the challenge of historically

particular data that mean different things to different people seems

to obscure Tambiah’s project. In terms of the ‘scientific’ practice

of fieldwork informed by Boas’ culture concept (the arrowed lines

in the internal framework of science in Tambiah’s chart), what are

the rules of the game, etc. most useful in examining these data? What

does scientific inquiry do with production of subjectivity by (produced)

subjects, anthropologically observed? Tambiah’s figure helps to provide

a framework in which the anthropologist might reflexively contextualize

his/her own work in relation to other scientific approaches, but doesn’t

seem to help move the anthropological discourse beyond ‘subjectively’

described ethnographic description based on fieldwork. What happens

to ‘reality’ testing?

Tambiah’s work also plays a useful role in showing the significance

of Boas’ ‘revolutionary’ culture concept through its inability to

fit neatly in his table: it’s difficult to make culturally specific,

interactive human data discrete and derive general laws from it. What

makes anthropology so epistemologically interesting is the variety

of data in the field (however defined) – the flux of experience (behavior,

habit), language and behavior – which can seem only loosely in accord

with the scientific community at large in terms of method (i.e. an

informed written record) and Tambiah’s internal framework – and which

data are as much shaped by the external context. The significance

of Tambiah’s internal vs. external paradigm analytically privileges

a historically consistent and internally realistic approach to scientific

knowledge but doesn’t seem to provide new approaches for Boasian culture-concept-carrying

‘scientific’ field workers. In anthropology’s attempt to move toward

an internal, logically consistent sociology of scientific inquiry,

it finds itself, employing Boas’ culture concept, cycling through

and articulating with external, social contexts.

Figure 1

The

Logic and Sociology of Scientific Inquiry

(Tambiah, 1990, p. 141)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hatch,

Elvin. 1973. Theories of Man and Culture. New York: Columbia.

Stocking, Jr., George W. 1968.

“Franz Boas and the Culture Concept in Historical Perspective.” In

Race, Culture and Evolution. N.Y. Free Press.

Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. 1990. Magic, Science,

Religion, and the Scope of Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.