Epistemology and Anthropology

Culture, the Individual, and Knowledge

in Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard

In this paper I want to examine both Evans-Pritchard’s and Malinowski’s

concepts of culture and the role the individual plays in the context

of epistemology, a theory of knowledge. Evans-Pritchard emphasized

the role of subjectivity as a lens with which to examine the behavior

of people, implicitly separating the study of natural science as a

field of study from the historical/cultural study of people; in contrast

to Malinowski, ‘individual’s’ motivations do not play a significant

role in Evans-Pritchard’s thought, but humans are also not automatons

of social structure. Malinowski assumed that Trobriand Islanders were

rational, self-interested actors, and framed his understanding of

the individual in terms of an elastic culture-concept of functionalism,

which had a number of key meanings for him, but which, for him, served

primarily to integrate the society. In this paper I want to contextualize

the implications inherent in these anthropologists’ theories of knowledge

within a broader map of epistemology and philosophy. I want to address

what Evans-Pritchard and Malinowski viewed as the ‘objects’ of their

study and where these conceptions might fit within a version of a

map of the way branches of knowledge relate to each other, drawn from

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (see map below). For the

purposes of this paper, I want simply to identify where anthropology

might situate itself epistemologically in terms of Evans-Pritchard

and Malinowski’s main approaches. I want to propose that while both

authors create stylistically ‘interesting’ anthropological accounts,

neither author can be said to have created a coherent approach that

comfortably or logically situates itself within the epistemological

categories of knowledge suggested by the map. By examining this map

of knowledge in relation to the work of these critical anthropologists,

I want to draw into relief both some of the strengths and weaknesses

of anthropological ‘knowledge.’ In Theories of Man and Culture, Hatch suggests that Evans-Pritchard may have developed an implicit concept of human free will based on his own religiously Catholic understanding of the individual: for Evans-Pritchard, “if the individual is not responsible for his actions Christianity is nonsense.”[1] E-P’s personal religious convictions are important as background, perhaps, but his sociological or theoretical views stand or fall independently of them. What is significant is that, associated with his views about the freedom of the human will, he is introducing into social anthropology the German idealist distinction between the cultural and natural sciences.[2] In the German idealist understanding, “ideas and human actions do not operate according to the laws of nature, and the cultural sciences are therefore fundamentally different from the natural sciences.”[3] Evans-Pritchard consequently develops an approach to anthropological study to produce a body of information one could call ‘knowledge’ based on a concept of human agency and an academic tradition, which he gravitated toward in an apparently unsystematic and somewhat arbitrary way. In fact, Evans-Pritchard argued that culture is best understood subjectively from the inside. Evans-Pritchard describes fieldwork as learning to think in their (‘the native’s’) categories and feel in their values. Evans-Pritchard takes the structure of their logic and argues that it has a coherency and logic. E-P regards subjective culture as having an internal coherence and validity which makes it compelling to the members of society; exotic beliefs and values can therefore be explained by making them intelligible to the nonbeliever. . . . E-P implies that all social institutions are to be viewed from the inside, for it seems that, to him, the phenomenal features of culture and society are manifestations of subjective factors. [4] By suggesting that

social institutions need to be viewed from the inside, Evans-Pritchard

makes clear that humans make choices, at least within limits, and

are not machines governed by the functional needs of the societal

institutions (as Radcliffe-Brown suggested). As a consequence, since

there are no specific institutions, or structures (which are as hard

as seashells according to Radcliffe-Brown) governing every human action,

causal explanation in anthropology becomes irrelevant and interpretation

becomes the most logical mode of understanding for the anthropologist.

Evans-Pritchard’s view of anthropological ‘objects’ of knowledge (see

map of epistemology below) as best perceived subjectively doesn’t

seem to entertain the possibility of multiple anthropological subjectivities

subjectively interpreting different perspectives of the same culture.

Hence his view seems to presume some sort of an ‘objective’ subjectivity.

Also, such reasoning doesn’t seem to allow for the possibility of

some kind of ‘contingently objective’ human actions, behaviors or

institutions. Some cultural phenomena may have universal features,

such as language[5],

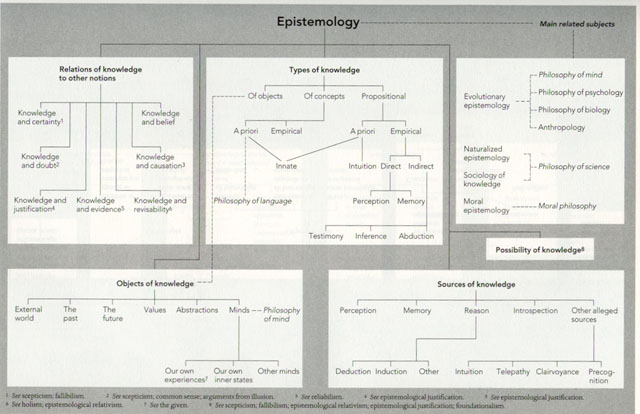

for example. According to Hatch, both Evans-Pritchard and Malinowski “built their theories on the premise that the individual must occupy a central position in anthropological thought, and in doing so they rejected the view that a person is not his own master. When they assert the autonomy of the individual, however, Malinowski and E-P are actually moving in very different directions, and they attack fundamentally different types of “determinism.” It even appears that they regard one another’s theories as prime examples of what they are against. Malinowski tended toward a cynical view of behavior, according to which the individual is conceived as using and manipulating culture for his own ends.”[6] Malinowski was probably reacting particularly against Durkheim who, according to Malanowski, posited that people slavishly followed custom, that the individual was culturally determined, and for whom human agency plays an insignificant role. Not only did Evans-Pritchard proffer an optimistic view of human behavior, he also believed that neither biology, nor culture, nor society, play a determinative role.[7] It’s a truism today to observe that views of agency and structure, based on unexamined or unreasoned assumptions may shape profoundly one’s interpretation in the same way that an unexamined determinism will, but these authors do not seem to examine the assumptions on which they ground their knowledge. While Malinowski’s assumption of self-interested motivation by rational actors who use culture to their own ends may fit more closely (than Evans-Pritchard’s conception of the human) within an evolutionary epistemology (see map below) – at times he argued that he was arguing from an ‘adaptational’ perspective - his suggestion of an elastic concept of ‘functionalism’ seems more to reflect an attempt to bridge a psychologistic interpretation of human behavior with functionalism than to explain individual human behavior within a group from an evolutionary perspective. In The

Oxford Companion to Philosophy’s map of epistemology, the author

identifies five main areas of knowledge -- ‘Relations of knowledge

to other notions,’ ‘Types of knowledge,’ ‘Objects of knowledge,’ ‘Sources

of knowledge,’ and ‘Possibility of knowledge’ – and one area of ‘Main

related subjects’ which includes “Evolutionary epistemology,’ (among

Naturalized epistemology, Sociology of knowledge and Moral epistemology)

and which, in turn, subsumes anthropology (among Philosophy of mind,

Philosophy of psychology, Philosophy of biology and Anthropology).

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy points out that any kind

of map is problematic;[8] nevertheless, maps

are also useful and they exist. In this paper, I want briefly to examine

some of the relations of knowledge charted in the map, to Evans-Pritchard

and Malinowski’s work.

Map of Relations between Fields of Knowledge Oxford Companion to Philosophy,

p. 931 Both of the above authors modestly and unsystematically engage in approaches to knowledge, which are touched on in this map, but possibly in an unreflexive and inconsistent manner. For the purposes of this paper, I want simply to identify where anthropology might situate itself in terms of Evans-Pritchard and Malinowski’s main approaches. In terms of ‘Types of knowledge,’ both seem to focus on knowledge of objects (see ‘Types of knowledge’ in chart), rather than concepts or propositional knowledge. In terms of objects of knowledge (chart, bottom left), both also seem to focus on a combination of many different aspects of objects of knowledge in terms of people in a dynamic context, including (see the map, bottom left) the 1) external world, 2) the past, 3) the future 4) values, 5) abstractions and 6) minds. Following the ‘Objects of knowledge’ on the map, Evans-Pritchard, in particular, focuses on 6c) ‘other minds’ in terms of 6a) his ‘own experiences’ and his 6b) ‘own inner states’; Malinowski asserts an assumption of the Trobriander’s own minds – rational, self-interested actors – which he then bases his observations of 1-6 on. As mentioned above, Evans-Pritchard and Malinowski construct concepts of numbers one through six within their own understandings of ‘functionalism.’ In terms of ‘Sources of knowledge,’ both authors seem to engage perception, memory and reason, as well as possibly introspection. Within ‘Scope of reason’ (see map), both do not seem to deduce, but rather to attempt to induce – to infer from the particular to the general[9] - but in a somewhat problematic way because what is general in anthropology is not epistemologically well-defined within the discipline. One could draw many more conclusions from this map of epistemology in relation to anthropology but space does not permit. By beginning to imbricate two anthropological theorists’ key concepts concerning the individual and culture with a mapping of the way different forms of knowledge relate to one another, I want to suggest that this is a potentially fertile area for examination. In addition, the evolutionary epistemological implications concerning the individual and culture for such anthropologists as Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard are undeveloped. For example, within an evolutionary framework, many scientists and thinkers argue that humans are ‘programmed’ in certain ways,[10] so the concept of culture and the individual would fundamentally transform themselves from both of the concepts of culture and individual which Malinowski or Evans-Pritchard engaged. In conclusion, both Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard offer a defining writing style for the discipline of anthropology, but the implications of their analytical approaches are not reflected in the context of the The Oxford Companion to Philosophy’s map of epistemology. On the other hand, it’s difficult to envision where the study of people fits into this map of knowledge, when the ‘objects’ of study are human beings interacting dynamically with others; this might potentially fit within ‘Objects of knowledge,’ particularly Philosophy of (body/)mind, and specifically: (body/)minds. The above map of epistemology begins to help to inform ways one might view the logical relationship between anthropology and epistemology, especially an evolutionary epistemology. Such an evolutionary epistemology has radical implications for an understanding of culture and the individual partially shaped by Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard. References Hatch,

Elvin. 1973. Theories of Man and Culture. N.Y., Columbia Honderich,

Ted, ed. 1995. Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford. Money, John. 1988. "Concepts

of Determinism" in Gay, Straight and In-Between: The Sexology

of Erotic Orientation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pinker, Steven. 1994. The

Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. New York: William

Morrow.

[1] Hatch, p. 242 [2] Hatch, p. 243 [3] Hatch, p. 243 [4] Hatch, p. 245 [5] See Pinker [6] Hatch, p. 350 [7] Hatch, p. 351 [8] Honderich, p. 927 [9] Honderich, p. 405, induction [10] Money,

p. 115-116: The threshold may apply to behavior attributable to

genetic programming, or to prenatal hormonal programming, or to

toxic programming, or to circulating hormonal programming, or to

pheromonal programming – pheromones being stimulating odors.

|